How we discovered 'breaking history news'

A revelation about the 19th century law driving 21st century abortion bans

For two hours on Wednesday, health care experts were glued to an audio feed piped out of a courtroom in New Orleans, as lawyers debated whether a widely used abortion pill should remain available.

That pill, mifepristone, was first approved by FDA more than two decades ago and is used in most U.S. abortions. A federal judge in April overruled FDA, and a three-judge panel in New Orleans is now weighing the appeal.

Here’s The Washington Post’s coverage of Wednesday’s hearing. The case is likely headed to the Supreme Court.

But the fight over mifepristone has raised an explosive question: whether the mailing of all abortion drugs is banned under an 1873 law known as the Comstock Act, which barred pornography, sex toys, contraceptives, abortion drugs and other “indecent” materials from being sent through the U.S. mail.

If so, that old law could be a backdoor to a national abortion ban.

“If a future president were to enforce these federal statutes, then they could shut down every abortion facility in America,” Mark Lee Dickson, an antiabortion activist who’s helped revive the Comstock Act in local ordinances around the country, told me.

The Biden administration has said that the Comstock Act is defunct and shouldn’t be used to limit access to abortion drugs. But some conservative judges have signaled they think the Comstock Act could apply in a world where Roe v. Wade has been overturned, and Republican lawmakers are warning pharmacies: a future administration could choose to invoke the law and “criminalize” people and companies for shipping and receiving abortion drugs.

Abortion-rights advocates say they’re growing anxious about the prospect. Women’s March, an abortion-rights coalition, put it bluntly: if Comstock is successfully revived to limit access to abortion drugs, “we’re f*cked,” the group wrote in an email to supporters last week.

Ann Marimow and I wrote about the emerging fight over the Comstock Act for The Washington Post, and you can read our story here:

A 150-year-old law could help determine the fate of U.S. abortion access

(And if you get the print edition, you can also find the piece on the front page of The Post today.)

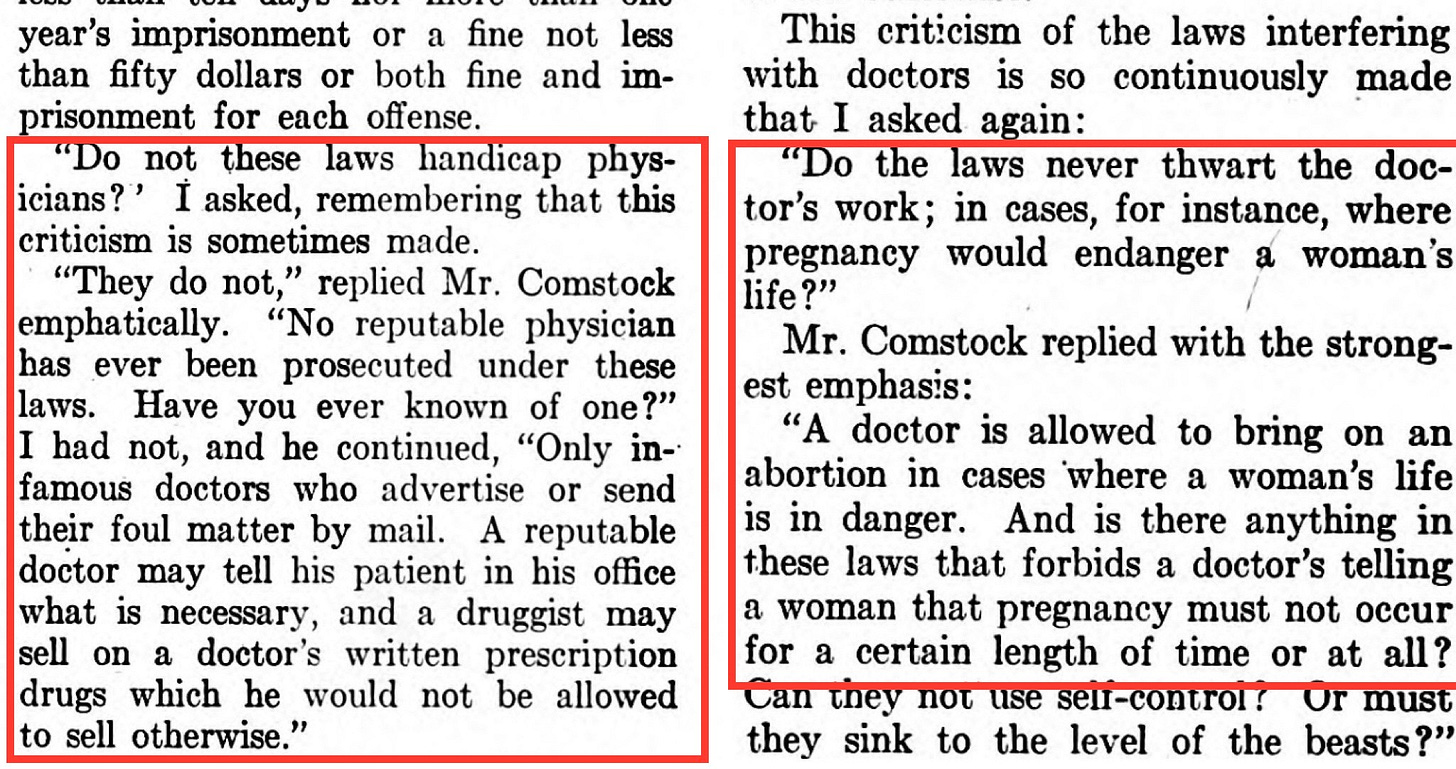

Our story includes a revelation: the author of the law, anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock, believed his namesake act should permit some abortions, including when the mother’s life was at risk — and seemingly when “a reputable doctor” prescribed the procedure.

Here are relevant excerpts from a Harper’s Weekly interview in May 1915, where the author was quizzing Comstock about criticism of his signature laws.

To some historians and legal experts, Comstock’s interview shows that he meant to draw a clear line between the “reputable doctors” he supported and the “infamous” abortionists he wanted to target.

Comstock’s comments about deferring to licensed physicians “says it all,” according to Anna Louise Bates, author of a biography about the vice crusader. “I think he would have thought that [abortion] was a matter for the family, the woman and the doctor to decide privately.”

Here’s some of the backstory on our story.

Behind our Comstock reporting

In early 2022, a smart source gave me a good tip: if Roe v. Wade falls, keep an eye on the Comstock Act.1

At the time, the law wasn’t on the national radar, though several experts seemed aware of it. Jonathan Mitchell, the lawyer behind Texas’ recent abortion restrictions, had hinted at the Comstock Act’s revival in his writing. Katie Keith, a lawyer who specializes in reproductive rights, invoked Comstock in public remarks on the day of the Dobbs decision.

And old rules had been recently revived to impose new goals. The Trump administration, led by Stephen Miller, resurrected a century-old rule known as public charge to limit immigration to the United States.

So I started looking into the Comstock Act, including speaking with former lawmakers who had tried and failed to repeal the law in the 1990s, worried about its implications.

“No one knew we were gonna roll back the clock, and [now] we’ve done it,” Rep. Pat Schroeder (D-Colo.), told me last summer as we discussed Comstock after Roe was overturned. “All you need are the right people deciding that’s how they want to spend their time and enforcement money — on women.” (Schroeder passed away this year.)

And I talked to a few legal scholars about whether Comstock really would apply today.

But the story stalled out. One complication: getting people to talk on the record last spring. Anti-abortion activists, focused on overturning Roe v. Wade and the immediate fallout, didn’t want to speak about hypotheticals. And abortion-rights groups didn’t want to tip their opponents to the possibility of using Comstock to limit abortion.

Well, everyone’s talking about Comstock now.

Earlier this year, my editor and I discussed reviving our own Comstock reporting, though it wasn’t clear what else needed to be written.

Was there anything new to say about Comstock, after the wave of explainers?

I thought it was worth taking a fresh look at Anthony Comstock, the anti-vice crusader who was so determined to impose his morals on America in the 1800s. I went to the library and checked out a few biographies; I read up on analysis of his signature laws.

In those write-ups, Anthony Comstock was often portrayed as a fierce opponent of abortions — a portrayal that’s been repeated in recent media coverage, and was reiterated in some of my interviews with experts.

But I found one reference to “Weeder in the Garden of the Lord: Anthony Comstock's Life and Career,” a 1995 book suggesting that the original Comstock Act was written differently than enacted into law. The book was out of print, and I couldn’t find a digital copy, so I set up an interview with Anna Louise Bates, the author, who explained her finding that Anthony Comstock originally intended to provide an exception for “duly licensed physicians” to prescribe abortion.

Bates — who told me that I was the first reporter to reach out to her, despite the resurgence of interest in the Comstock Act — also sent along screenshots of a few pages from her book, which included a citation for an interview that Anthony Comstock did with Harper’s Weekly in 1915.

I asked Bates about the citation, which seemed like a promising lead. Bates said she didn’t have the Harper’s Weekly interview, hadn’t looked at it in decades, and wasn’t sure of the exact date — but she was confident that Anthony Comstock spoke to the magazine and addressed the original intent of his law.

So I went through the Harper’s Weekly archives to find that interview. The result was more than I expected: Anthony Comstock explicitly saying that he supported some abortions. I then shared the document with historians and legal scholars across last weekend, double-checking that our read was right.

It’s hard to know how much to weight Anthony Comstock’s 108-year-old comments or what he’d say about the mifepristone fight; he’s not exactly available for a fresh interview!

And I want to be cautious — if one old interview is out there, in plain sight, perhaps we’ll discover others that will shed further light on Anthony Comstock’s beliefs. I’m certainly looking for additional documents now. (If you have any leads, please send them to me!)

Of course, what Anthony Comstock intended 150 years ago probably matters less than how courts interpret his signature law today.

But as a reporter who tries to break news about what’s coming next, it was fascinating to unearth a “scoop” with the help of historians. Especially when the future of abortion in America is being shaped by legislation from our distant past.

My initial response to that source a year ago: What’s the Comstock Act?

If you’re scouting for potential fresh leads re: Comstock (as fresh as leads can be w/regard to 19th century legislation, that is!)...reach out to the Lower East Side Tenement Museum in NYC. Their educators have long included references to the Comstock Act in various tours/presentations, and they’re well-versed on the topic. But even more importantly, the museum is *very* well connected with various historians who might have more to offer.