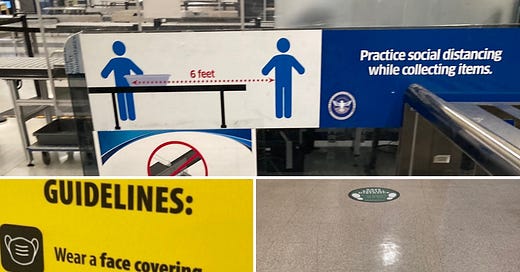

For months, I’ve been keeping track of covid-era warnings still posted in stores, around office buildings, even on sidewalks around Washington, D.C.

The signs that we all treat as invisible, even though they’re right in front of us, exhorting people to stay apart.1

At The Washington Post, I wrote last week about how we got all those six-foot-apart signs, and leaders’ growing acknowledgment that there was scant science behind choosing — and importantly, sticking with — that distance.

From that article:

“It sort of just appeared, that six feet is going to be the distance,” Fauci testified to Congress in a January closed-door hearing, according to a transcribed interview released Friday. Fauci characterized the recommendation as “an empiric decision that wasn’t based on data.”

…

Experts agree that social distancing saved lives, particularly early in the pandemic when Americans had no protections against a novel virus sickening millions of people. One recent paper published by the Brookings Institution, a nonpartisan think tank, concludes that behavior changes to avoid developing covid-19, followed later by vaccinations, prevented about 800,000 deaths. But that achievement came at enormous cost, the authors added, with inflexible strategies that weren’t driven by evidence.

The article took some heat, including from people in the public-health community who said the story should’ve better reinforced the benefits of social distancing, or underlined how six feet alone wasn’t actually enough protection.

Some of that criticism struck me as fair; writing a newspaper article isn’t like solving a math problem, and there’s no one way to get to the right answer. Could a story have had extra quotes, or included more context, or even been structured differently? I’m always open to that.

I’m less inclined to agree with some accusations that arrived on social media or in my inbox, particularly from people who said the story shouldn’t have been written because it harmed public health, or imagined nefarious motives behind it. One college professor emailed to ask if I received “instructions on how to write that from your new bosses.” (Definitely not.)2

More than four years after covid’s arrival, it’s important to acknowledge what went right, what went wrong, and what we’ve learned.

Yes, social distancing saved lives, particularly during covid spikes. Yes, you were safer six feet apart than two feet apart; every bit of distance helped. Yes, when I see someone who is sick today, I try to be physically away from them too!3

Yes, the six-foot distance was chosen based on the initial theory that covid was mostly spread by droplets that people were coughing or sneezing out, drawing on flu-fighting tactics.

It was a well-intentioned guess in the middle of a world-altering, life-threatening public health crisis.

But the government’s recommendation to stay “six feet apart” for more than two years, rather than opt for a different distance — say, “three feet apart,” as some other countries or the World Health Organization effectively pursued — had real consequences. We know that now.

It took too long to adjust to the reality that covid was airborne, and that six feet of social distance wasn’t going to be enough; we needed to adopt other mitigations like ventilating buildings and wearing high-quality masks. A lot of Americans didn’t get that message.

It took too long to acknowledge the impact on schools, despite well-regarded experts quickly and repeatedly calling for changes. This smart New York Times article by Emily Anthes captured the debate, all the way back in March 2021. (Federal officials did loosen the social distancing guidance for schools a few days later, but many schools still didn’t reopen for months.)

I wrote a detailed story last week about the two doctors leading Congress’ covid committee and wrestling over what it means to “do no harm.”

The decision to stick with six feet of social distance caused some harm, particularly given that many schools had to stay closed because they couldn’t accommodate that distance between desks. But they could’ve accommodated three feet of distance, and likely staved off some of the nation’s learning loss and other bad consequences of having schools shuttered. There’s no way to overlook that.

Experts who have advised the president have said as much.

“It never struck me that six feet was particularly sensical in the context of mitigation,” Dr. Ashish Jha told The New York Times in that March 2021 article.

Jha went on to serve as President Biden’s national covid coordinator a year later. He has continued to call the persistence of the six-foot-rule one of the bigger mistakes of the pandemic.

Since the pandemic began, public health experts have been under attack — often unfairly.4 I’ve written about false claims around vaccines and politically motivated threats to the broader field.

But one threat to public health right now is credibility. It’s on reporters to tackle the field’s mistakes and miscommunications too — and not to pretend they don’t exist, like the social-distancing signs that still pepper my city, and that we all collectively ignore.

It reminds me of a trip to South Korea years ago, where I ended up wandering a Seoul neighborhood covered in English-language street signs. A local told me the signs had been put up for the 1988 Olympics but were never taken down. Will our six-feet-apart warnings be with us for decades too?

The story’s goal was to summarize how leaders like Tony Fauci had increasingly admitted that six-feet of social distance for covid protection wasn’t rooted in some scientific calculation, and include some fresh reporting on the behind-the-scenes fight four years ago.

The story was also envisioned as a tight piece, focused on the newer revelations and Fauci’s pending appearance in Congress, particularly because the benefits of social distancing have been repeatedly detailed, for years.

And when I say tight piece — I’ve learned in my time at The Washington Post that length really does matter; we think in inches for stories, because there are only so many inches available in the print newspaper. (It’s the first thing I think now when I see complaints on social media that The Post or The New York Times didn’t include certain context in a story; sometimes a story is only budgeted to be so long, which I didn’t realize before joining a news organization that has such a strong print tradition.)

But since this is my Substack, and there’s no digital limit on how much I can blabber, I’m happy to share a bit more about how last week’s story came to be. I think I first pitched a story in 2022 about revisiting the six-foot rule and how it was devised; I’d heard about some inside-the-administration fights and doubts. But the story never got done. There were other, more immediate crises to pursue such as Mpox, I wasn’t sure if I could break much new ground, and then I went on paternity leave.

I got interested again after Fauci privately testified to Congress in January 2024, saying on record that he wasn’t aware of any scientific basis behind a six-foot social distance. Knowing that Fauci was returning to Congress in early June, and learning that he would be publicly pressed on social distancing, I tried to find fresh details about the fight.

As I wrote back to that college professor, the only person pushing for the article, and the details within, was me.

Also: It’s not my nature to argue at length on Twitter, and I’m not particularly inclined to highlight angry reader emails, unless they’re truly silly or nasty. (I think Washington Post reporters, by nature of our jobs, are going to receive wild accusations, even from normally sober-minded people.) But some claims I’ve received or seen, like there were no drawbacks to choosing a six-foot distance, or that only Republican critics care about this issue, are just not true.

Unless it’s my toddler.

One recent example: Fauci was wrongly accused by The Daily Mail of having “made up” the six-foot rule, and Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene parroted that accusation during her questions at a congressional hearing. The six-foot recommendation was crafted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, not Fauci.